Pipe Major Kenneth John MacKenzie Baillie

Pipe Major Kenneth John MacKenzie Baillie:

A Nova Scotian Gael Abroad.

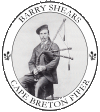

Kenneth John MacKenzie Baillie, also known as Kenny or Major Baillie, was born at Pictou in 1859 a month after the accidental death of his father. His parents were John Baillie, born 1816, a native of the Parish of Clyne, Scotland and Catherine Walker (b.1825) a native of Pictou. Baillie was raised in the Gaelic-speaking home of his uncle at Balmoral, and he received his first military experience as a boy bugler with the militia while training for the Fenian Raids. He learned to play the violin as a youth, and while still in his teens he and his brother left Nova Scotia for Boston ostensibly to work in a relative’s tailoring business. His violin teacher may have been the well-known local fiddler, Robbie MacIntosh. Robbie was born in the Paris of Rogart, Scotland in the early 19th century and settled with his parents in Earltown, Nova Scotia, in 1822. In 1860, Robbie was invited to perform for the visiting Prince of Wales in Halifax, and received a hat from the Prince’s personal wardrobe for his music. Robbie was also an exceptional dancer, and would often finish his musical performances by step-dancing and playing the violin at the same time, a skill revived by a few Cape Breton fiddlers in the late 20th century.

Figure 1 Robbie MacIntosh, the famous Earltown fiddler

MacKenzie Baillie was unhappy with his work in Boston and eventually shipped aboard a cattle boat for England. In 1878, at the age of nineteen, he enlisted in the Royal Marine Artillery, a corps that “lived with the navy but fought on land” (The Evening News, n.d.). In addition to being an excellent violin player, Baillie also played the uilleann pipes and Scottish Lowland pipes, musical skills developed while he served abroad and in Britain. He made all his own reeds for the instruments, a skill he learned from his father-in-law, Pipe Major Sandy MacLennan. Baillie also made several violins during his retirement in Nova Scotia.

A musician was a valuable asset on a ship during the age of sail and according to one source, many ships in the Royal Navy had a fiddler on board, and later a piper was also included.

“In the days of sail, when steam was quite a luxury in a man-o-war, the musician of the ship was a recognized fiddler, whose primary duties consisted in encouraging the sailors who were ‘manhandling’ the capstan bars or manning the falls while hoisting boats, by playing airs on his fiddle to which the men would keep regular rhythm with the tramp, tramp of their feet; but with the disappearance of sails and the personality of the fiddler, came the advent of the piper with his strathspeys and reels”…In the Navy it is not uncommon to hear the skirl of the pipes reverberating from the surrounding hills of some landlocked harbour after the ships have dropped anchor and the ship’s companies have settled down to the evening routine.” (Malcolm, p. 243)

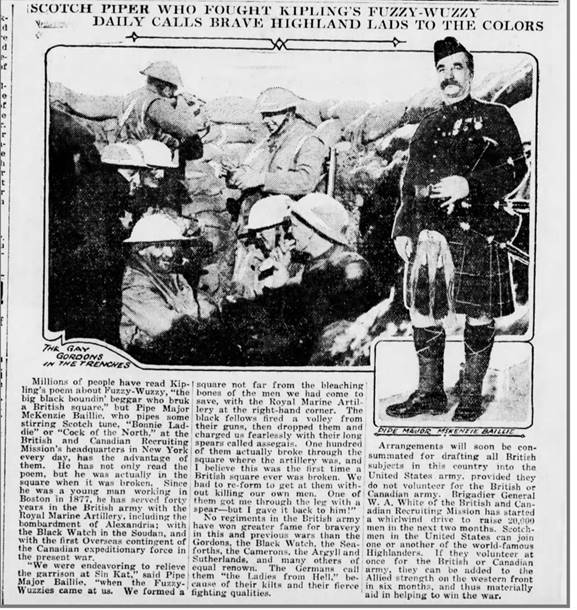

Baillie had an outstanding military career, which included being part of the marine compliment of the HMS Temeraire in Egypt and the Sudan, in 1880-1884, and took part in the bombardment of Alexandria and the relief of Khartoum. During an expedition to the Sudan Baillie’s Royal Marine Artillery was paired with the Black Watch and dispatched to relieve the British garrison at Sin Kat. By the time Baillie and the others arrived they found nothing remained of the garrison but “a pile of their bones bleaching in the sun.” The Sudanese soon attacked Baillie’s column which had hastily formed a British Square to repel the enemy. On the right hand corner of the Square was the artillery, while in the centre were camels, supplies and the sick and wounded. Despite the superior firepower of the British, the Sudanese attacked the Square armed mostly with spears and managed to break through the square, a feat which later inspired the poem Fuzzy Wuzzy by Rudyard Kipling. Reduced to hand to hand fighting during the exchange, Baillie received a spear wound through the leg but the Sudanese dervishes were later driven back and the square reformed. This was reputedly the first time a British Square had ever been broken.

The late 19th century was the age of “gun-boat diplomacy” and Baillie served on board several ships during this period. He was on board HMS Inflexible, which was the first ship in the British navy outfitted with electric lights, and HMS Eurylas on the African west coast. During the Niger River expedition the British captured King Jaja, a slave who had bought his freedom and, due to his control over the lucrative palm oil trade, became one of the most powerful men in the eastern Niger Delta at the time, and a thorn in the side of mercantile interests in Britain. At this time plam oil was used in candle making and to lubricate machinery during the Industrial Revolution.

Baillie also served aboard the HMS Calliope, was one of the last two corvettes powered by steam and sail in the British navy. In 1889 it was dispatched to Samoa as part of the Royal Navy Australian Squadron to protect British interests in the Pacific. During a Samoan hurricane in 1889, all ships of a Royal flotilla were lost except Baillie’s HMS Calliope, known later as “The Hurricane Jumper”. The hurricane wrecked twelve of the thirteen ships anchored in the harbour including three warships from both Germany and the United States. The storm was so intense that its aftermath and destruction was described by well-known author Robert Louis Stevenson as: [There was] “no sail afloat and the beach piled high with the wrecks of ships and the debris of mountain forests.” When the ship returned to port Baillie piped Queen Victoria aboard and according to family lore, her Majesty immediately appointed him Pipe Major. Naval historians will dispute this story, but it should be noted that, at the time, the title of Pipe Major was an appointment, and not a specific rank, and so the story does have merit.

During the Boer War, Baillie was involved in recruiting work in Glasgow and in 1903, after retirement, he and his family returned to Nova Scotia, settling at Loganville, Pictou County. After Baillie’s return to Nova Scotia, piping became his life’s work and he taught piping to several individuals in northeastern Nova Scotia.

Shortly after his return to Nova Scotia, Baillie was appointed Pipe Major of the 78th Pictou Highlanders, replacing Walter Beaton. In 1909 he won first prize in his regiment for rifle shooting. In 1910 he accompanied the 78th for training in Camp Aldershot, Nova Scotia. There were 3500 men in camp that year, including eight bands. Since Baillie was also an accomplished literate fiddler, he no doubt also influenced the fiddling repertories of several pipers who also played the violin. These included Dan Rory MacDougall, Ingonish, Kenny Matheson, River Denys, pipers with the 94th Regiment and Angus ‘the Ridge’ MacDonald, Lower South River, a piper with 78th Highlanders, as well as others.

Figure 2 MacKenzie Baillie, Pipe Major of the 78th Pictou Highlanders

In 1913 Pipe Major Baillie accompanied the pipe band of the 78th Pictou Highlanders to Charlottetown for the Orangemen’s Annual Celebration on July 12. The following excerpt from the Charlottetown Guardian gives some background to Baillie’s early career as a piper:

“PM Baillie, Loganville of the band of the 78th Highland Regiment, who with other pipers, played here at the Orangeman Annual Celebration on July 12th, and who on Monday evening excellently sustained an entire concert program at a performance in the Caledonian Club’s Hall, where he showed himself to be a master of the Scottish people’s national musical instrument, acquiring his wonderful skill with the bagpipes in a purely inconsequential way, taking it up first as a past- time. This was when he was serving with the Royal Marine Light Artillery, in which he enlisted. But soon the yearning to make himself proficient in the playing of the pipes grew upon him, and he got himself appointed recruiting sergeant for that corps in Glasgow, solely for the purpose of improving his playing ability, by studying under the best bagpipe players of that city. Afterwards he went to Inverness to perfect himself in the music of the pibroch. Subsequently, to such a high standard of skill had he attained, he took part in a bagpipe competition in London, against some of the leading pipers of the Metropolis, and secured the first prize. Since then he has had many triumphs in bagpipe playing and has won medals in the foremost competitions throughout the United Kingdom.

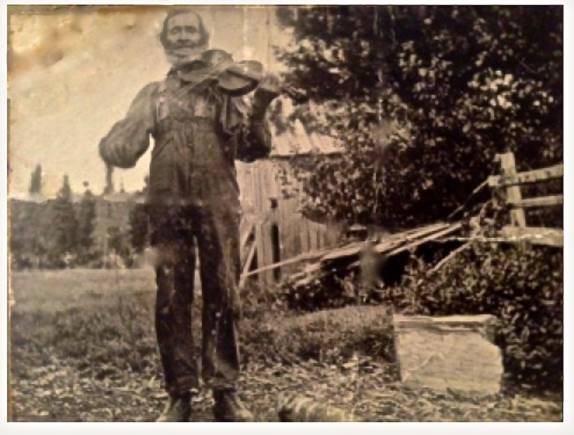

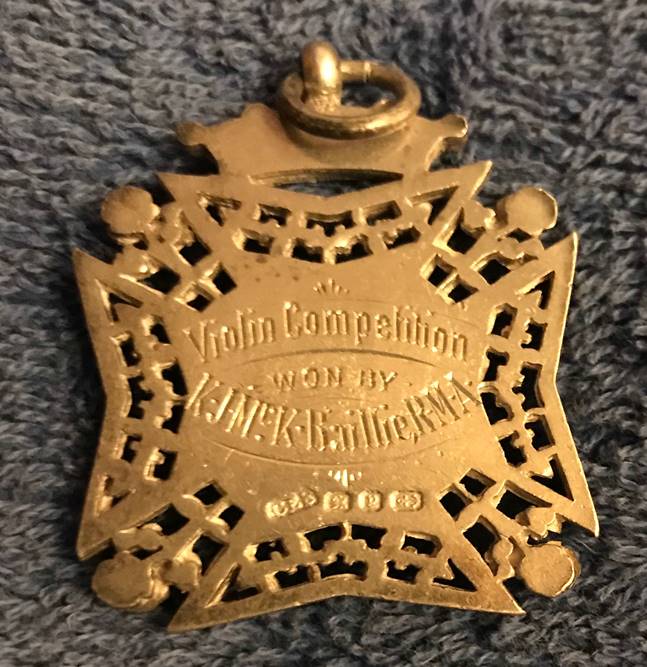

Baillie was the first native-born Nova Scotian to win awards at several competitions in Scotland for both light music and pibroch, (and fiddle contests), as some of his medals indicate.

Figure 3 some of Baillie's unmarked gold medals for piping

Figure 4 1st Prize for Piobaireachd

Figure 5 1st prize for pipe music

.

Figure 6 2nd place for march playing (medal reverse)

Figure 7 2nd place for marches (front view)

Figure 8 1st place for violin playing Glasgow 1888

Figure 9 Glasgow 1888 (reverse)

Pipe Major Baillie’s musical career was as equally impressive as his military one. After his return to Nova Scotia, he toured extensively with a troupe of entertainers before the First World War and in that capacity performed on the concert stages of many North American cities as a piper and Scottish violinist (Baillie also played the Irish or uillean pipes). Baillie’s obituary describes his work location simply as Vaudeville. His tour itinerary in 1911 lasted five months and included stops in three Canadian cities and fourteen U.S. cities.

1911 concert tour:

| June 6 | Orpheum | Minneapolis |

| June 13 | Orpheum | St. Paul |

| June 20 | Orpheum | Winnipeg |

| June 27 | Orpheum | Calgary |

| July 4 | Orpheum | Vancouver |

| July 11 | Orpheum | Seattle |

| July 25 | Orpheum | San Francisco |

| Aug. | Orpheum | Oakland |

| Aug. 8 | Orpheum | Los Angeles |

| Aug. 22 | Orpheum | Salt Lake City |

| Aug. 29 | Orpheum | Denver |

| Sept. 5 | Orpheum | Lincoln, Nebraska |

| Sept. 12 | Orpheum | Omaha |

| Sept.19 | Orpheum | Des Moines, Iowa |

| Sept. 26 | Orpheum | Kansas City |

| Oct. 3 | Orpheum | Sioux City |

| Oct. 11 | Majestic | Chicago |

| Oct. 17 | New Palace | Milwaukee |

| Oct. 24 | State Lake Theatre | Chicago |

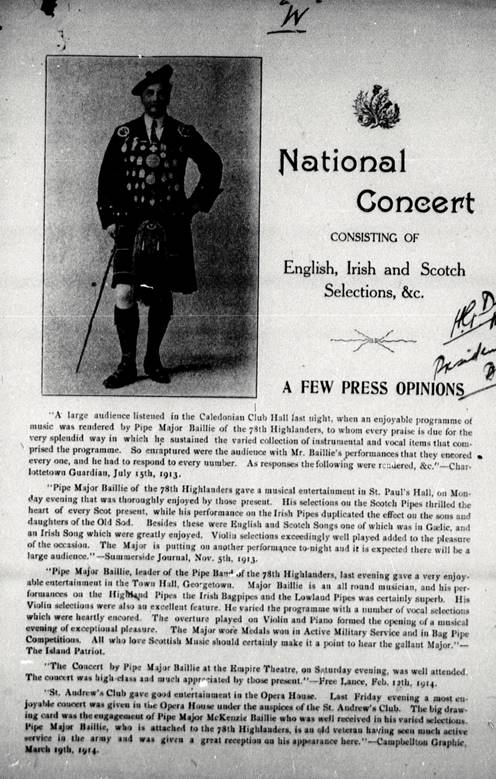

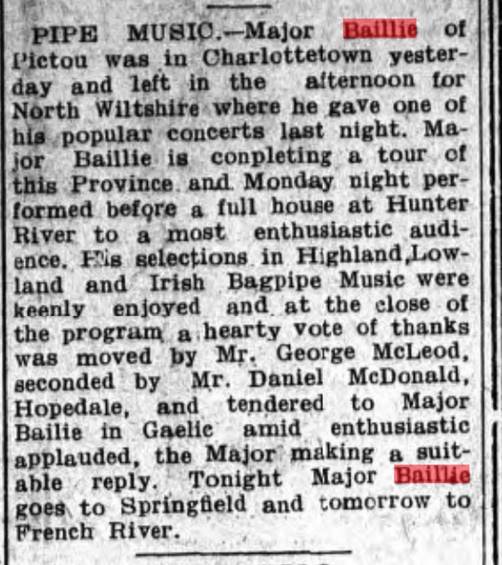

His 1913 tour was a bit closer to home and featured concerts in Summerside and Georgetown and included Baillie singing songs in both English and Gaelic, in addition to his performances on violin and various bagpipes, a virtual one man “ceilidh”.

Concert Reviews

Figure 10 Concert announcemnet with reviews c. 1913

Figure 11 PM Baillie, c. 1913 from a publicity post card.

Figure 12 Charlottetown, PEI , newspaper clipping. c, 1913

The following year he performed for the St. Andrews Society in Campbellton, New Brunswick.

Baillie was Pipe Major of the 17th Battalion during World War One, and despite his advanced age of 57, he accompanied the unit to England. Although Baillie was well past the normal age for overseas duty his skill as piper coupled with his better than average physical condition secured him a role in the conflict.

This was a low period in Baillie’s career. While intoxicated one evening he was arrested for punching an officer in the jaw, and subsequently court martialed. This event was most likely the inspiration of the story I heard from the late Peter Morrison, Sydney, during one of my interviews, in which Baillie was threatened with a demotion in rank and the removal of his Pipe Major’s stripes from his uniform. According to Morrison, Baillie replied to this threat saying “Queen Victoria, put them there and only she could take them off!” The circumstances surrounding the incident were vague and since the officer was wearing a raincoat that evening and his rank concealed, it was argued Baillie didn’t know he was an officer. After the trial he was demoted to private from sergeant, sentenced to 6 months detention, and later returned to Canada as medically unfit. The punishment could have been much worse. Baillie was excused from hard labour due to his age and passed his time in detention composing music, although his original tunes have not survived. After his return to Canada he spent the rest of the war recruiting in communities across Nova Scotia and while still wearing his Pipe Major’s stripes. In 1918 he was part of the stage play “Getting Together” performing in New York alongside three other veterans of the war. The cast was on a recruiting drive in the United States, along with the tank Britannia. Baillie’s image was featured in several recruiting notices carried in several newspapers in the United States like the one featured below:

Figure 13 USA Newspaper recruitment article, c. 1918

While in New York, Baillie would play the bagpipe every day at 220 West 42nd Street, or from the back of an automobile, as part of the government’s plan to raise 20,000 men in two months for service in Canadian and British units overseas. The soldiers performed recruiting tasks during the day and then without even so much as a costume change went on stage in the evening: “Pipe Major Baillie is pretty busy, because during the day he uses his pipes to inspire Scotchmen to enlist in the British or Canadian army, and in the evening he is exceedingly decorative, and as musical as a piper can be” (New York Tribune, Mar. 17, 1918). After the war Baillie continued to perform as a vaudeville musician and while in New York in May 1922 recorded a selection of marches accompanied by Nathanial Shilkret on piano. This recording as well as another made in in October 1922 was never released and according the discography was destroyed. The first recording featured two competition style marches. “Ross’ Farewell to the Black Watch” and “Leaving Glenurquhart.” The second recording was for the eight steps in strathspey and reel time for the “Fling” and included standard tunes for the time which included “Balmoral Castle”, “Devil in the Kitchen”, “When you go the the Hill take Your Gun” and the reels “MacDonald’s” and “Cameronian Rant”. The surviving recording also made in October 1922 featured Ross’ Farwell to the Black Watch and Miss Elspeth Campbell on one side and “The Lads with The Kilts” and “The Sword Dance” on the other. The 78-RPM recording was made shortly before Baillie succumbed to cancer and according to one of his students it represents but “a shadow of the man’s playing ability” (interview, Alex Sutherland, 1988). Due to failing health Baiile used a bellows bagpipe (reel pipe) for this recording.

The Baillie family lived in a large house at Loganville, the site of one of the biggest tanneries in the Canadian Maritimes; the building was formerly used as a boarding house for workers in the tanning industry. Since Pipe Major Baillie was away a good deal of the time, either touring as a musician or with the army, Catherine Baillie and their son “Sandy” tended the farm with the aid of several local boys and a young girl from Britain who was part of the Child Immigration Scheme in the early 20th century. In many cases the boys would perform chores in exchange for piping lessons and Mrs. Baillie, who was descended from a long line of MacLennan pipers, taught a lot of boys to play the bagpipe.

The MacLennan family of Inverness was renowned for its pipers. Baillie’s father-in-law, Alexander or “Sandy”, was descended from the 16th-century MacLennan town pipers of Inverness. Sandy’s grandfather, Duncan, was a piper at Waterloo in 1815, and Sandy’s great grandfather, Murdoch, was a piper at Culloden in 1746. Sandy MacLennan’s father Donald “Mór” MacLennan received some instruction in piping from the celebrated MacKays of Gairloch, before the MacKay family immigrated to Pictou in 1805, and he was highly sought after as a piping tutor. Donald Mór taught some very prominent pipers in the early 19th century, such as John “Ban” MacKenzie and Donald Cameron, in addition to his two of his sons, Sandy and John. Sandy won the Prize Pipe (a bagpipe awarded for the best performance in competition) at Inverness in 1857 and the Gold Medal in 1860.

Figure 15 PM Sandy MacLennan

Sandy’s younger brother John MacLennan was piper to the Earl of Fife and he was also an Inverness Gold Medalist, having won the Prize Pipe in 1848 and the medal in 1854 (B. MacKenzie) (A recent list of Gold Medal winners shows John winning the Gold Medal in 1867). Sandy MacLennan enlisted first with the 78th Highlanders and was Pipe Major from 1843–1850, before transferring to the Inverness-shire Militia. Both gold medals came to Canada with family members in the early 20th century. I remember seeing Sandy MacLennan’s gold medal in a small Pictou County museum in 1973 (its present whereabouts are unknown) and John’s gold medal remains in the family.

Figure 16 John MacLennan's Inverness Gold Medal (G. Shears Collection)

Sandy’s daughter Catherine (born 1861) was also an accomplished musician. She could play both the bagpipe and piano and, according to one account, she was a better piper than MacKenzie Baillie, who she later married.

Catherine learned piping from her father at a time when female pipers in Scotland were generally frowned upon. It is a great pity women were not permitted to compete in piping competitions in Scotland until well into the 20th century. If women had been permitted to play against men, the history of piping would have a much different dynamic. Catherine’s method of chanter instruction to her students was via William Ross’ 1880s Collection of Bagpipe Music and she often sang the Gaelic words to many of the tunes. Her list of pupils included several prominent pipers in Nova Scotia such as Alex Sutherland, later of Dartmouth, Sandy “Air” Sutherland, Diamond, Pictou County and the Henderson brothers of Camden, Colchester County.

Catherine and her husband had a daughter who died in infancy and was buried in Scotland. When Catherine came to Nova Scotia she brought with her several pieces of furniture, a piano and all her late father’s awards and Highland regalia. These included an English officer’s sword recovered by one of her ancestors, possibly Murdoch, from Culloden’s battlefield, the prize pipe and the Inverness Gold Medal, an award presented by the Highland Society of London and still coveted by pipers today. She often remarked to her piping student, Alex Sutherland, how much she missed her little cottage in Inverness.

Not much else is known about Catherine MacLennan Baillie, other than a few recollections of her life in Pictou County. Catherine Baillie died in 1927 two weeks after suffering injuries from a fall. It was reported at the time that she had an exceptionally large funeral, complete with prayers in Gaelic.

Figure 17 Catherine "MacLennan" Baillie, c. 1920

Sandy Baillie continued the musical traditions of his parents and was a popular piper and violinist in the Maritimes. He married Jenny MacRae of Prince Edward Island, and together with their oldest son, MacLennan, formed a dance band playing regularly at local dance halls in Colchester and Pictou Counties. Like his father, he served in the army during the First World War and was later Pipe Major of the Pictou Highlanders. Sandy was one of those amazing musicians who could pick up a tune by ear, after only hearing it played a few times. He carried his bagpipe and violin in a single case specially designed to accommodate the two instruments. It was said of Sandy Baillie that he had the biggest pipe case in the Pictou Highlanders.

Pipe Major MacKenzie Baillie and his wife Catherine had a profound influence on the musical landscape of Nova Scotia in the early 20th century. Piping in many areas of rural Nova Scotia at the end of the 19th century had remained virtually unchanged for several generations, but was already showing signs of decline. By the start of the 20th century traditional piping, like the Gaelic language, was in decline and the influence of these two Gaelic-speaking pipers rekindled an interest in piping, especially in Pictou and Colchester counties. By the early 20th century pipers in Nova Scotia were being exposed to a musically literate form of bagpiping through contact with the Baillies as well as several recent immigrant pipers from the Scottish Lowlands. The Baillie family of Pictou County were at the forefront of these changes, especially on mainland Nova Scotia, and through their pupils helped transform piping from its older, aural method of transmission to one of modern musical literacy.